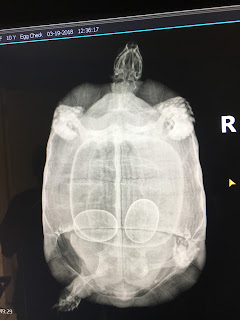

The owners were concerned that she may have been "egg-bound" because this breed of tortoise generally lays 3 eggs. To determine if she was harboring any more eggs, we took radiographs of her which revealed she had 2 eggs yet inside! After consulting with an exotic vet specialist, she was deemed healthy and the owners were made aware that it may take up to 3 months for "Georgie" to lay the remaining eggs. Unfortunately, "Georgie" is an only-tortoise-child, so her eggs are unfertilized and have no embryo.

The Golden Greek Tortoise, Testudo graeca terrestris, belongs to the Family Testudinidae. Testudinidae is a terrestrial family usually with distinguishable high, domed shells, and un-webbed feet. The un-webbed feet and stumpy legs aid in body support and movement on land. The high-domed shells are also known to provide protection from predators. Testudo graece is found in the Mediterranean basin, ranging east to Iran with some populations in North Africa, southern Europe, and east Asia. This species also has temperature-dependent sex determination. T. graece is distinguishable by its smaller and paler appearance than other Testudo species, has a high-domed shell, and has a yellow spot on either side of the head.

Works Cited

van Dijk, P.P., Corti, C., Mellado, V.P. & Cheylan, M. 2004. Testudo graeca. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2004: e.T21646A9305080. Downloaded on 30 March 2018

Gibson, Richard, and Durrel Wildlife Protection Trust. “A Guide to the Identification of Tortoises in the Genus Testudo.” British Chelonia Group, 1 Jan. 2018, www.britishcheloniagroup.org.uk/caresheets/identity.

Pough, F. Harvey. Herpetology. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Publishers, 2016.